Both the Chaos of Jackson Pollock and the Sterility of Photorealism are Incompatible with Christianity

Unveiling the middle ground where faith, philosophy, and beauty all meet in the person of Christ, image of the invisible God.

Authentic Christian art strikes a balance between abstraction and realism, rejecting the extremes of Abstract Expressionism—where meaning dissolves into unrecognizable chaos—and Photorealism, which reduces reality to soulless or meaningless matter. Rooted in a worldview shaped by faith and philosophy, the Christian artist uses partial abstraction to blend naturalistic forms with spiritual depth, revealing the soul and invisible truths of existence. This tension, distinct from modern art’s dualistic pitfalls, defines its unique purpose and beauty.

Above: John the Baptist, by David Clayton, 21st century.

The Limits of Abstraction and Naturalism

If a painting of a man is so abstracted that it is not recognisably what is meant to be—as is the case with Abstract Expressionism —then put simply it is a bad painting. There can be no Christian Abstract Expressionism. On the other hand, extreme naturalism, such as we see in Photorealism, is also bad art from a Christian point of view because it reflects an attitude that says there is no meaning or spiritual dimension in what we are looking at, only matter. There is no Christian Photorealism. Christian art sits between these two poles of dualism. It has traditionally aimed to reflect naturalistic appearances so that we know what we are looking at, but to stylise the image through partial abstraction to suggest to the observer the invisible aspects of what we see, such as its meaning and importance, and in the human person, the soul.

The Profound Connection Between Faith, Philosophy, and Art

A painter's artistic choices are not made in a philosophical or theological vacuum. Rather, an artist's ‘worldview’—his ‘personal philosophy’ or understanding of reality that combines philosophical and theological truths—profoundly shapes what he paints and how he depicts it. At a more general level, everyone possesses an underlying philosophical framework that informs his perceptions and judgments, whether he recognises it or not. This "worldview" also determines an artist's decisions when he paints, including what he deems worthy of imitation and the specific stylistic techniques he employs to emphasise those aspects of reality that matter most to him. Therefore, a Christian artist must have a correct worldview; otherwise, he might lead people astray and misrepresent aspects of the faith through his paintings' content and style.

Lessons from Ancient Greece

Ancient Greek philosophy can help us here. Ancient Greece was a great cauldron of ideas. Indeed, there are so many ideas that it could be argued that just about any personal philosophy we encounter today was represented in some form by the ideas of at least one of those ancient Greek philosophers. Many of those ideas of ancient Greece passed into Roman civilisation, and the best of them, subsequently, into mainstream Christian thought. Of course, two Greek philosophers stood out as giants: Plato and his greatest student, Aristotle. Together, they came closest to describing the nature of man, God, and the world through natural reason alone and without the benefit of Revelation.

Plato, Aristotle, and Christian Thought

The ideas of these two philosophers have continued to be of great interest to Christians because the philosophical methods of inquiry they developed have helped Christians understand more deeply what Christ revealed to us and how it can be applied in everyday life today and in the past. Perhaps the Christian who did more than any other to integrate Christian teaching with Aristotelian and Platonic thinking and the Fathers who preceded him is St Thomas Aquinas (1215-1274 A.D.), who integrated their philosophies with the gospel.

Raphael’s School of Athens: A Visual Parable

To illustrate the continued importance of the ancient Greeks to Christian thought, consider this painting. It is called the School of Athens, and it was painted in 1511 by the Italian artist Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483-1520), generally known in English as Raphael. His painting is on a wall in the Vatican, in the official residence of the Pope, the Apostolic Palace.

It shows many great philosophers of the ancient world. Despite the name of the painting, not all of them lived in Athens. Indeed, some are not even Greek, but collectively, they represent the tradition of philosophy that originated in Athens and lasted over 1,000 years from about 600 BC. At the centre, featured most prominently, we see these two great figures already mentioned, Plato and Aristotle. Raphael has shown Plato pointing upwards to the metaphysical world, what we might call the spiritual world, which exists beyond the material realm (which he called the world of Ideas or Forms). Plato is talking to Aristotle, who is pointing downwards to the earth to symbolise his more significant interest in the goodness and reality of the material realm of existence.

The Eternal Tension in Art

This detail of a great painting symbolises the tension in all art: that is, how do we describe the relationship between the spiritual and the material worlds, especially when painting people, between body and soul? Some people believe that the essence of human nature is what we think and feel. An artist who believes this might dispense with the portrayal of the human body and try to represent pure emotion, thought, or subconscious aspects through abstract shapes (20th-century abstract artists did this, for example). The ethos of the abstract expressionists is testable - we can present people with these paintings to a hundred people (who haven’t studied art history at university) and ask the question that only 5-year-olds dare ask…what is it? If the majority respond with the artist's intention without being told in advance, then we can concede a point to them. However, in my experience, few, not even the critics who promote their work, seem to see what the artists hope to portray.

Above, from top; Jackson Pollock No 1; Mark Rothko, Untitled

At the other extreme, some people, called ‘materialists’, believe that man is only made of matter and has no soul. An artist who is a materialist might decide to paint the man in perfect correspondence to natural appearances, as close to perfect in every visible detail as possible, but would have no interest in communicating that he possesses a soul or that a painted scene has a meaning that indicates a Creator or loving God. If executed skillfully, such a painting or sculpture would be dazzling in its lifelike detail but sterile and lifeless in appearance, like a death mask or an image created mechanically without human artifice. Photorealism is an example of the art of the materialist. For example, I invite the reader to look at the work of Ron Mueck, who sculpts in an extreme form of photorealism called Hyperrealism (it is difficult to find photos that can be reproduced here).

Was this done by a man or a machine?

The distinction between some naturalistic styles of authentic Christian art and materialist art forms, such as photorealism, is not always obvious to the casual observer because the idealisation used by the Christian artists in naturalistic styles, such as 17th-century baroque art or High Renaissance art (such as the art of Raphael), is often subtly applied. However, as a rule of thumb, if you look at an image and you are unsure if it is a photograph or a painting, then we have lost the necessary element of human artifice in creating the image. Below is a photorealist painting by artist John Baeder. It is difficult to tell if we are looking at a photograph or a painting!

The Christian Synthesis: Body and Soul

The Christian traditions of art are different from both of these extremes. Authentic Christian art is based upon the premise that man is a profound unity of body and soul in a single person. To reflect this, the Christian artist will paint the person in a style between the two extremes. So, in his painting, there will be enough correspondence to natural appearances that we know what we are looking at. However, the artist also deviates partially from natural appearances to communicate to us by visible means truths that would otherwise be invisible, such as the existence of a soul in man. This takes great skill, for he must communicate through his art that the person is alive and has thoughts and feelings through the depiction of what is, necessarily in painting and sculpture, the depiction of a single static moment.

Mastering the Craft: Gesture and Expression

This could be done through vigorous gestures or facial expressions from which we can read moods and emotions. This reflects what we all know, that we know what a person is thinking and feeling through how he expresses it through the body. The precise way in which the artist does this always reflects, to some degree, personal decisions. These decisions characterise and lead to recognisable styles in painting. It is how we can distinguish, for example, a Rembrandt from a Michelangelo. Each deviates from the rigid portrayal of natural appearances by partially abstracting in their own way, and we learn to recognise the pattern of how each does it by looking at his art. Rembrandt is known for his ability to reflect a mood in the person through subtle and skillfully rendered facial expressions. Here is a famous self-portrait of his for example. Notice how so much of this representation is shrouded in shadow and mystery and indistinctly represented; this is the partial abstraction. He saves the detailed and precise rendering for the face and the eyes, rendering them more naturalistically. The result is a harmonious balance.

Similarly in this painting of Mary Magdalene by Georges de La Tours painted in the 17th century, notice how much of the scene is shrouded in deep shadow and indisctincly rendered. The idealisation is subtle but it is there. Through the contrast of light and dark, the artist communicates the message that the Light overcomes the darkness. This was a deliberate artifice of baroque art, the style that both Rembrandt and de La Tours painted in.

Icons: Windows to the Divine

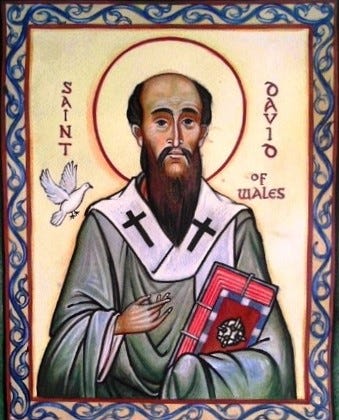

In traditional iconography, a whole tradition of sacred art developed to communicate theological truths also. The goal of the iconographer is to show man in union with God in heaven, shining with the uncreated light of divinity, due to a participation in the divine nature (which is on offer to all Christians). This is done through many different visual devices that result in the characteristic style, but to give one example: in this icon below, the heavenly realm is suggested by seeking to eliminate a sense of depth and let the image live in the plane of the painting. This flatness symbolises a truth about heaven, that it is outside time and space. It is not a literal representation necessarily; rather, it is a partial abstraction designed to communicate an idea about a place we cannot see.

Above: St David of Wales, painted by David Clayton

Naturalism and Idealism in Harmony

In art, we call correspondence to natural appearances ‘naturalism’ or sometimes ‘realism’; and how the artist deviates from natural appearances ‘idealism’ or ‘symbolism’ because this is how he directs our thoughts to a non-material and invisible ideal. Christian art imitates nature by balancing naturalism and idealism to move towards a deeper reality reflecting both the material and spiritual realms.

Modern Art’s Dualistic Trap

Nearly all contemporary and modern art reflects, in some way, the errors of a dualistic worldview, veering too far towards either the immaterial or the material. But this does not mean that Christians should disregard it altogether. Pius XII wrote of this in his encyclical Mediator Dei. He was writing about the criteria for art in churches, but drawing on principles that apply, for the Christian, to all art. He wrote:

"Nor is it to be admitted that sacred images and pictures should imitate nothing of the realism of nature, or that they should be distorted into an extreme symbolism which is hardly intelligible to the Christian people. For sacred art ought to express the mysteries of the faith and the examples of the saints in such a way that the faithful may be moved to veneration and imitation, and may understand more easily the truths of religion. Hence the more recent custom of depicting sacred subjects in a manner that is alien to the traditional practice of the Church is not to be approved where it departs from this norm; yet neither is an excessive realism to be commended which debases the dignity of sacred persons or renders the mysteries of faith less noble and sublime." (Mediator Dei, 188)

Engaging Modern Art with Discernment

Therefore, the Christian can engage with modern culture and art, drawing in what is good, true, and beautiful and rejecting what is contrary to the gospel, in harmony with the needs of the community that will see it. So, while I do not accept for a moment that the art of the abstract expressionists communicates anything profound about human nature or God, I do see some beauty in some of their work, which is almost an accidental occurrence and despite, not because of, their ethos.

Some of Rothko’s floating shapes are reminiscent of a landscape, and Jackson Pollock’s random squirts of paint on canvas have at times the beauty of a polished marble slab (although this was not their intention). I was quite happy, therefore, to create a decorative piece of work based upon a Rothko myself. I painted this for our dining room.

I aimed to harmonise with the colours on the wall. Painting this was not in any way an exercise in self-expression. Further, I deny that it reveals anything profound about human nature or the angst of modern man. Therefore, although inspired by Rothko, it is absolutely not Abstract Expressionism. If we presented this to a hundred people and asked, ‘What is it?’, I would expect a range of random answers. This is because it isn’t meant to represent anything. Rather, to the degree that it is successful (I’ll let you decide), it is decoration. I classify it as decoration at the same level as the drapes and chair cushions. Not that this makes it unimportant. On the contrary, good decoration is a vital component of any beautiful space (and therefore far more critical to the Christian life than Abstract Expressionism will ever be!). Incidentally, I incorporated Boethian mathematics in the design, using his formula for harmonious proportion described in De Institutione Arithmetica and inspired by the book that Plato clutches in the Raphael painting, The Timaeus. It is acrylic on canvas and 36”x36”.

Above: This is Decoration and Does Not Express My Feelings or Emotions; acrylic on canvas by David Clayton, 2023.